Team CB On Ground: Observations from DS Group’s CSR Work in Udaipur, Rajasthan

Over the years, having been part of assessment teams for social programmes, I have had the opportunity to closely observe a wide range of interventions across rural India. While many are well-intentioned, fewer are meaningfully aligned with local realities, and rarer still are those that recognise the continuity between people’s decisions to stay or migrate, decisions deeply influenced by the availability and quality of water and land (particularly for small landholders), livelihood opportunities, and an often overlooked sense of security and belonging.

It is also important to acknowledge that CSR programmes in India have steadily evolved over the past decade. A growing, though still limited, number of corporates are moving away from isolated, compliance-driven projects towards more integrated and holistic approaches that attempt to address interlinked socio-economic factors over time. This transition is uneven and remains a work in progress across sectors and geographies, but where it is attempted sincerely, its effects tend to show up not immediately in metrics, but gradually in behaviour, confidence, and planning horizons.

My recent visit to Udaipur, walking through the blocks of Kurabad, Alsigarh, and Jhadol Phalasia, offered insights into how some corporate groups are beginning to better understand how a theory of change materialises at the grassroots. It reaffirmed the view that sustainable impact cannot be achieved through single-sector or one-off interventions, but through a portfolio of connected efforts that respond to lived realities.

What follows is a concise yet in-depth account of first-hand observations of the social interventions undertaken by the DS Group in Udaipur as part of their corporate social responsibility initiatives.

Water conservation as a foundation

The first site I visited was a check dam in Kurabad. Having seen many such structures across states, some functional, many abandoned, I approached this one with a fair degree of scepticism. On its own, it did not appear particularly different.

However, my perspective shifted when a few farmers in the area pointed to wells that now retain water deeper into the year. They spoke about wheat cultivation becoming viable where it was once uncertain, and mustard now being planned for the coming season. One farmer mentioned that while soybean had suffered damage this year, maize had helped cushion the loss. What stood out was the presence of planning and the conversations about sequencing crops, allocating water, and sending children to school with greater regularity. Despite subtle probing, there was little complaint, which in my experience is often telling.

The company claims that across the region, 462 soil and water conservation structures have created over 17.6 lakh cubic metres of water storage. The difference seemed to lie in how these structures are embedded within farming systems rather than standing apart from them.

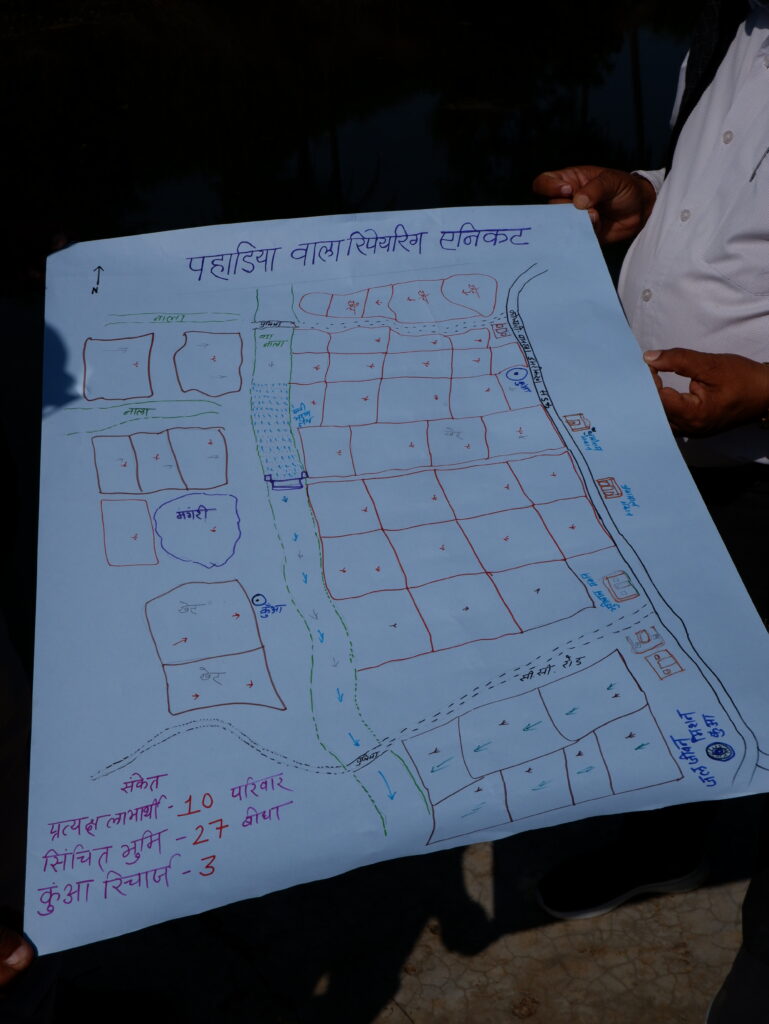

The Water Economic Zone approach in Alsigarh watershed reinforced this impression. The area is divided into multiple micro-watersheds, with phased work across watersheds 9, 10, 12, and 14. Structures such as gabions slow water flow from the Angloi Mata Tatla towards the Sabarmati, ensuring more perennial availability downstream. Importantly, less intervention has been done in forest areas, indicating a degree of ecological restraint often missing in watershed projects.

Collective irrigation brought shift from individual to group decisions

Group-based solar lift irrigation systems have further strengthened the water narrative. Farmers are collectively running these irrigation systems, meetings are held to form maintenance groups, and a membership deposit is collected from everyone to fund the upkeep and maintenance of these systems. Interestingly, these meetings are quite critical aspect of shared resource management.

From what I observed, these systems have reduced operating costs and introduced the necessary skill of negotiation, prioritisation, and shared accountability, elements that technical solutions alone cannot deliver.

Designing agriculture around constraints

Most farmers I met operate small, fragmented, largely rainfed landholdings. Any agricultural intervention that ignores this reality tends to fail, regardless of how technically sound it appears on paper.

Here, improved practices seemed consciously designed around these constraints. Intercropping models such as maize with soybean or urad were promoted not to maximise yield, but to reduce risk. Efficient irrigation tools like sprinklers, drip systems, rainguns were introduced selectively, based on water access, rather than uniformly distributed.

Here, improved practices seemed consciously designed around these constraints. Intercropping models such as maize with soybean or urad were promoted not to maximise yield, but to reduce risk. Efficient irrigation tools like sprinklers, drip systems, rainguns were introduced selectively, based on water access, rather than uniformly distributed.

Centralised Bio Resource Centres (BRCs) play a significant role in this ecosystem. At these centres, Jeevamrit and natural pesticides are prepared using locally collected organic waste. Farmers purchase these inputs directly and receive training on pest management, particularly relevant for soybean and vegetable crops that are prone to infestation. Preventive measures are emphasised, and according to field teams, success rates over the past two years have been high.

The value of these centres lies not only in what they supply, but in what they reduce: dependence on distant, often unreliable markets and chemical inputs that farmers may not fully understand or safely handle. It is worth noting that pesticide spraying is still largely done by men in the household, with only minor precautions taken, an area where continued engagement and safety education remain important.

Also, high-value crops such as strawberry, turmeric, ginger, and safed musli have been introduced selectively. Trellis systems, multi-layer farming, and the WADI model are supported by training and demonstration farms.

Also, high-value crops such as strawberry, turmeric, ginger, and safed musli have been introduced selectively. Trellis systems, multi-layer farming, and the WADI model are supported by training and demonstration farms.

Millet promotion stood out as a return to crops suited to local agro-climatic conditions rather than an introduction driven by external trends.

Village-level Kisan Samitis and Custom Hiring Centres play roles that are often underestimated. Beyond machinery access, they provide forums for discussion around cropping choices, water use, and input planning.

Groups such as the Jai Ambe Kisan Samiti prepare and sell natural pesticides made from locally available plants like dhatura, neem, castor, and sitafal leaves. Local volunteers provide technical support, and meetings are held regularly to manage operations.

As per the company, over 3,300 farmers are directly engaged across the three project locations, and 132 rural entrepreneurs have emerged.

The Ganga Maa model follows a unique design simplicity. A circular patch divided into seven sections allows for seven different vegetables to be grown simultaneously, enabling staggered harvesting throughout the week. Brinjal, tomato, and chillies are most common. One such garden can support the nutritional needs of 10 to 12 families, making it especially suitable for households with very small land parcels.

In Gudli village, Shivlal Patel’s oil extraction unit reflected another important principle: retaining value near the source.

Shivlal had earlier migrated to Mumbai for scrap work. On returning, he needed an enterprise that matched both local supply and local demand. With training, financial planning support, and branding assistance, he established a small oil mill.

Today, he claims to earn somewhere between Rs 25,000 and Rs 30,000 per month. Farmers now bring oilseeds to his unit instead of selling them outside the village. Processing, income, and trust remain local.

Such enterprises often fail due to weak market positioning. Here, attention to packaging and visibility seems to have made a measurable difference.

Practical design for women’s work

In many programmes, women’s labour is acknowledged rhetorically, but rarely reduced in practice. The introduction of maize shellers and improved sickles here addressed a very practical need. Women spoke about time saved and reduced physical strain during peak agricultural seasons.

Stitching centres and dairy-linked activities provide supplementary income aligned with household responsibilities. One skilled woman tailor I met now earns approximately Rs 350 per day, having transitioned from field labour. Orders come in bulk through linkages with local garment shops.

A closing reflection

Having seen many programmes over the years, I have learned to look for what is not immediately visible. In Udaipur, the most telling sign was not any single intervention, but the absence of urgency in people’s voices.

Farmers spoke about the next season, not the next crisis. Entrepreneurs spoke about continuity, not survival. Migration was discussed as a past necessity rather than a present plan.

From a practitioner’s perspective, that shift usually indicates that something is working—not loudly, but steadily.

A Note of caution and possibility

These observations are based on interactions with a limited number of farmers, entrepreneurs, and field teams over a short visit. They do not constitute a quantitative assessment, nor a structured qualitative evaluation. What is presented here are first-hand experiences shaped by who we met and what we were able to see.

One limitation that stands out is the absence of visible collaboration with other corporates operating in the same geography. Whether by choice or circumstance, the work appears to be carried out largely in isolation. There is potential value in partnerships that could deepen reach, share learning, or reduce duplication in a region where development needs remain high.

Similarly, while individual interventions align well with local realities, there is scope to further integrate these efforts with existing government schemes. Greater convergence across irrigation, agriculture, livelihoods, and enterprise development could strengthen sustainability and expand access to public entitlements without creating parallel systems.

These reflections do not detract from what is already in place. Rather, they are the kinds of questions that emerge when a programme demonstrates consistency and intent on the ground. From experience, it is usually at this stage when systems begin to function and trust is established that deeper integration becomes both possible and necessary.

Kunal Barua is a seasoned communication strategy professional with a particular focus on social impact and sustainable development. He has over a decade of experience across film production, event management, retail branding, and strategic communications, and has worked with prominent brands like Samsung and Bridgestone. In all his fields of professional engagement, he has a strong track record of supporting meaningful initiatives that blend purpose with performance.